Virtual Reality in Veterinary

Dr Chris shares some nerdy thoughts on how Virtual Reality may impact the veterinary sector.

Dr Chris shares some nerdy thoughts on how Virtual Reality may impact on the veterinary sector.

Animal Realities

The future of veterinary medicine is one that embraces a range of emerging technologies, from Virtual and Augmented Reality to Artificial Intelligence.

The future of veterinary medicine is one that embraces a range of emerging technologies, from Virtual and Augmented Reality to Artificial Intelligence.

Written for AIMed Magazine in 2018

What does the veterinary surgeon, or indeed clinic, of the future look like? Whilst the actual clinician and patients themselves are likely to look much as they do today, the impact of a number of emerging technologies on the way they go about training, examining, diagnosing, treating and managing their clinical work is almost certain to be profound. From Virtual and Augmented Reality (VR & AR) to Artificial Intelligence (AI) these technologies are already changing the way human doctors practice medicine and there is no reason to believe that veterinary will be any less transformed.

There are already exciting glimmers of what is to come, from the use of VR and AR in vet schools to help students better understand anatomy to AI being applied to first opinion, primary veterinary care provision through smart kiosks, freeing up overstretched veterinarians to focus on the truly vital aspects of their work and enhancing the client and patient experience in the process.

Virtual Reality

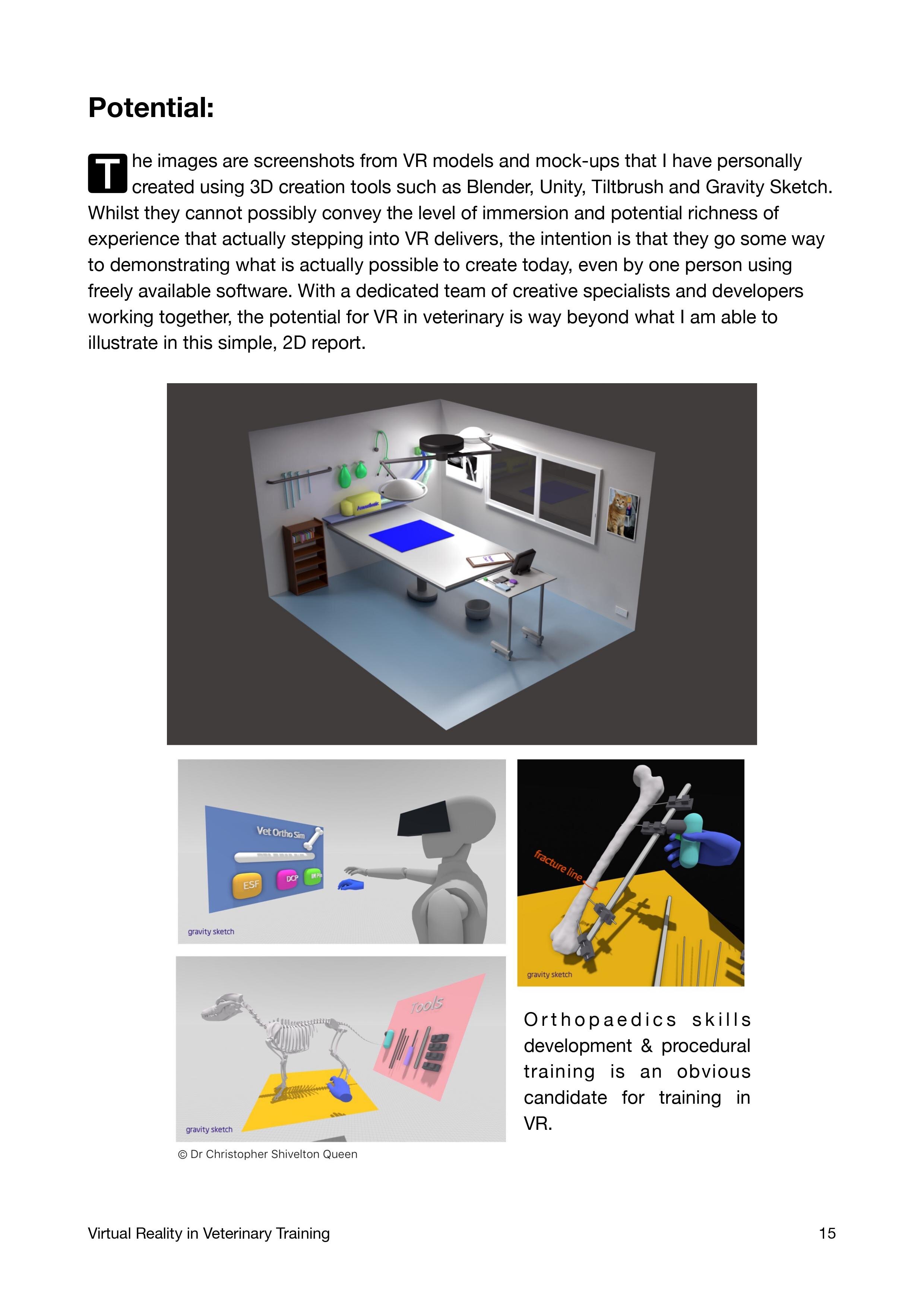

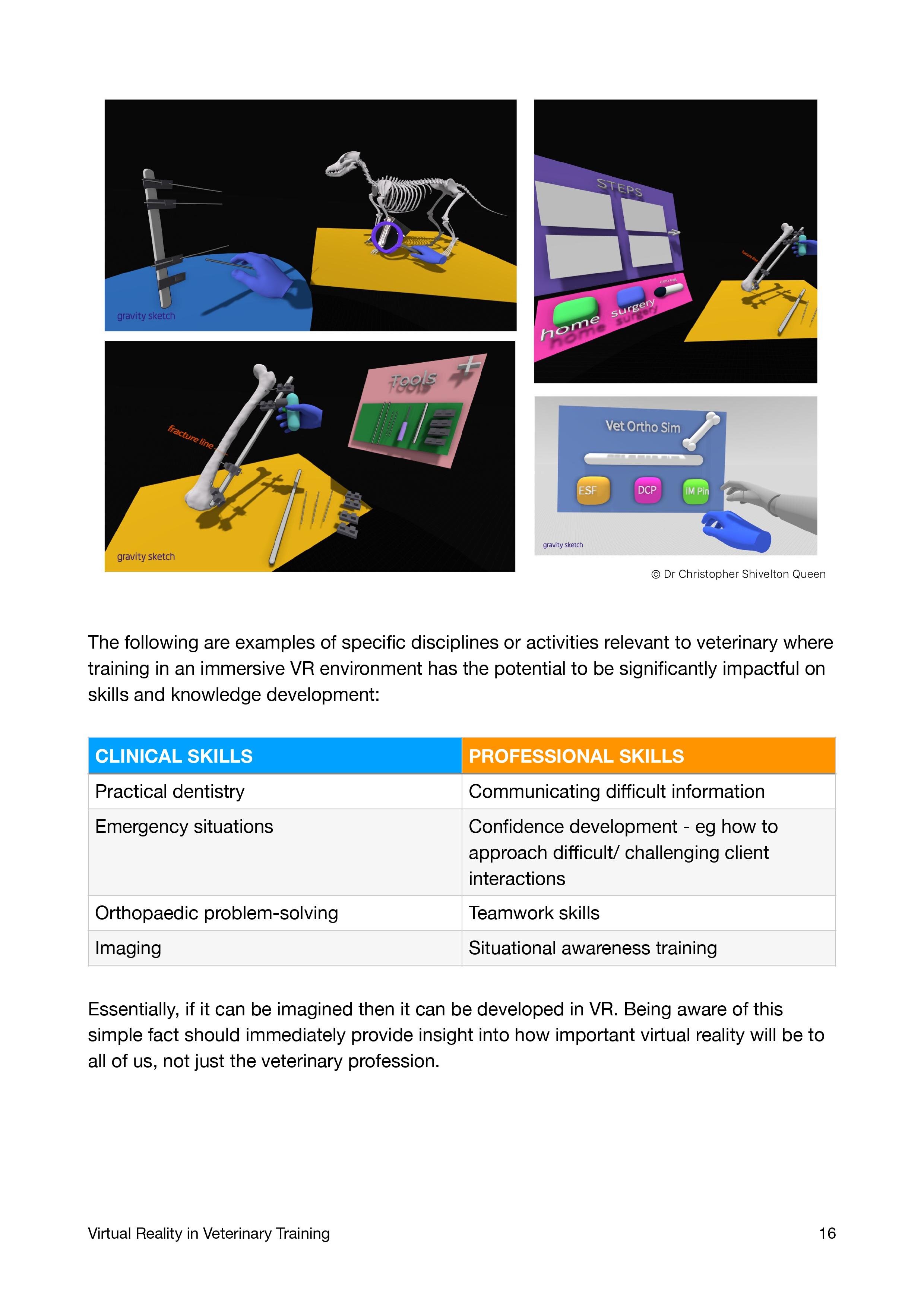

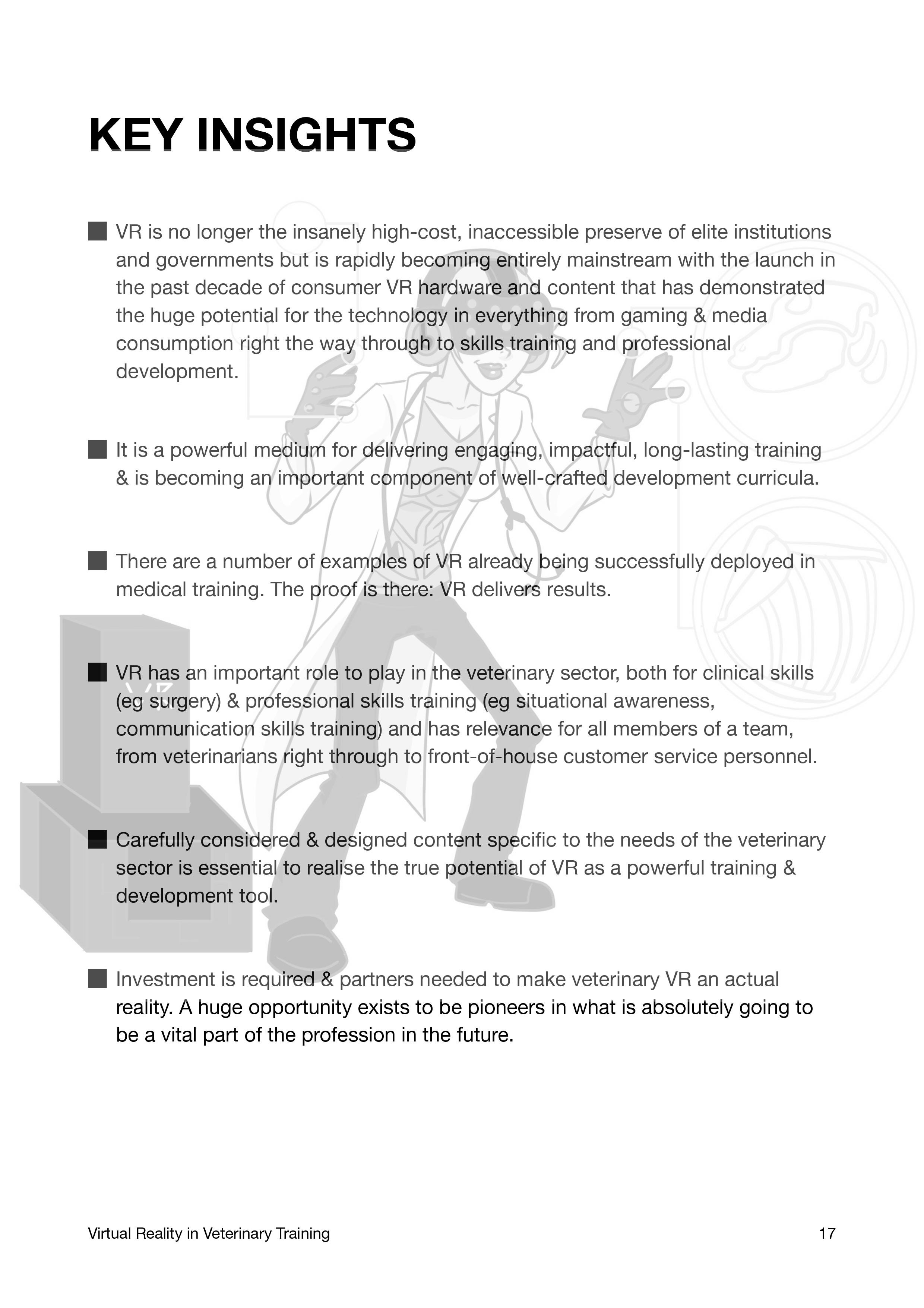

VR has been proven to be an effective tool in training, especially in situations where the knowledge may be complex, impossible or prohibitively expensive to experience in the real world, dangerous or involve understanding of very spatial concepts and development of specific psychomotor skills. For years surgeons have trained using haptic-enabled VR simulators that enable them to handle real keyhole surgical instruments but with the difference being that the patients being trained on are a combination of physical model and digital simulation, culminating in the illusion of actually performing a specific procedure. The benefits of simulations is that they can be intentionally altered, for example by introducing an unexpected complication, as may occur in the real surgery, tracked for accurate feedback on skills development and the exercises repeated multiple times without any risk to an actual patient. Solutions that dispense with physical haptic tools, such as OssoVR’s orthopaedic training simulations, delivered via consumer VR systems such as the Oculus Rift, have proven so effective in training new surgeons that multiple residency programmes have adopted them for student training.

One of the best examples of a haptic simulator specifically designed to deliver veterinary training that I have seen to date is the Haptic Cow and Horse developed by the University of Bristol’s Professor Sarah Baillie. This uses a combination of finger-tip force-feedback haptics and a visual digital simulation of the anatomical structures being palpated to train veterinary students in the vitally important skill of accurate rectal palpation, which is used for everything from reproduction assessment in cattle to detection of potentially lethal colic in horses.

Veterinary surgeons undertake a plethora of procedures, from day one skills such as routine neutering to complex soft tissue and orthopaedic surgeries. Learning any procedure for the first time currently requires a combination of traditional textbook study, observation of a more experienced colleague, practice, if possible, on models or post-mortem specimens, ultimately leading to assisting in the procedure initially and ultimately developing the skills and confidence to become the primary surgeon. This process can, and does, take a long time, is often incredibly stressful and usually requires significant investment. Keeping skills fresh and updated once acquired can also prove challenging if there is not a steady, reliable stream of patients requiring said specific procedure. VR training offers an alternative, one where the training veterinarian simply dons a headset and is guided through a simulated version of the same procedure, in the process learning vital spatial awareness and muscle memory of the steps involved, whilst developing autobiographical recall on account of having actually carried out the procedure over and over again, all in the realistic, immersive yet ultimately repercussion-free environment of the simulated world.

Augmented Reality

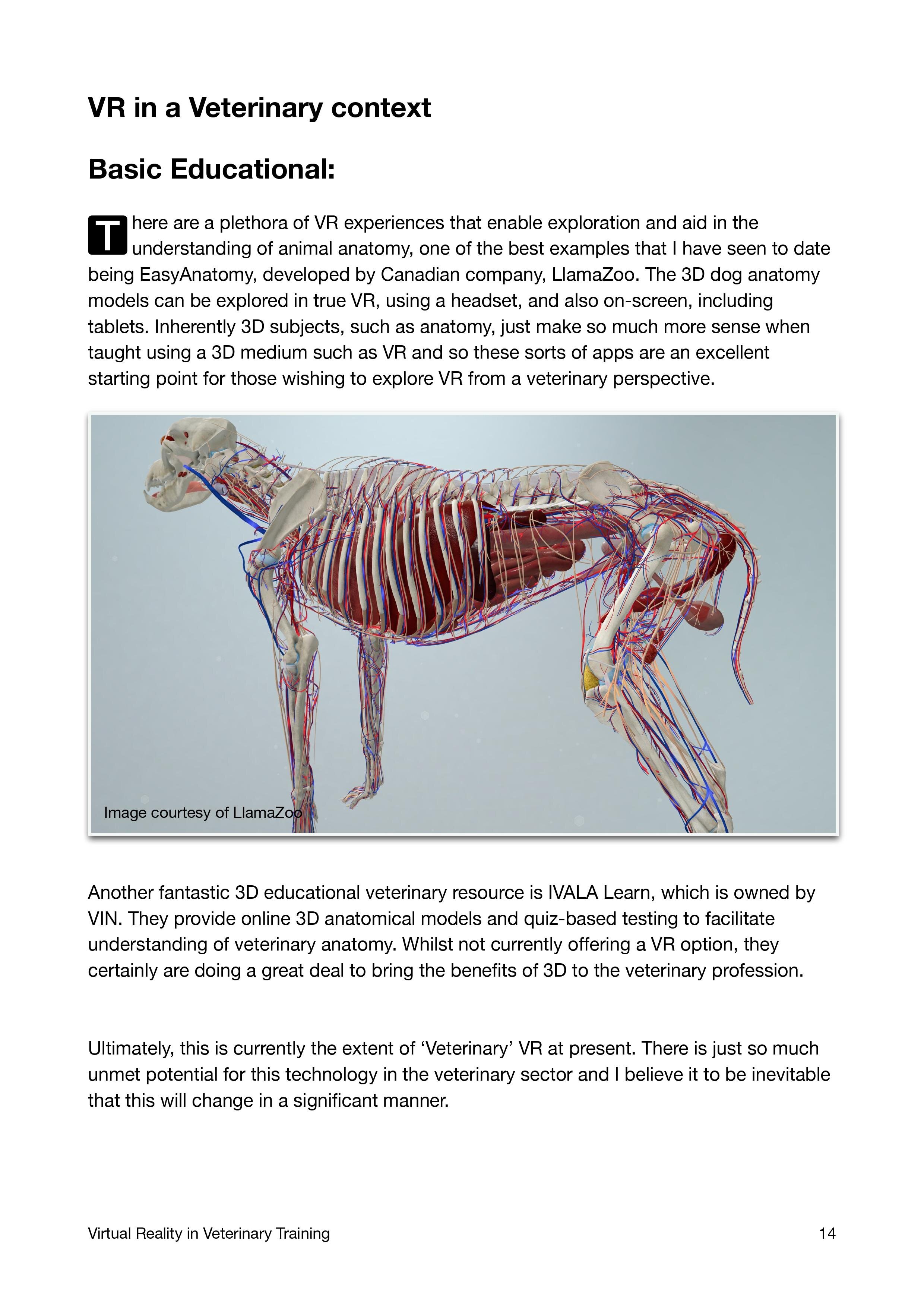

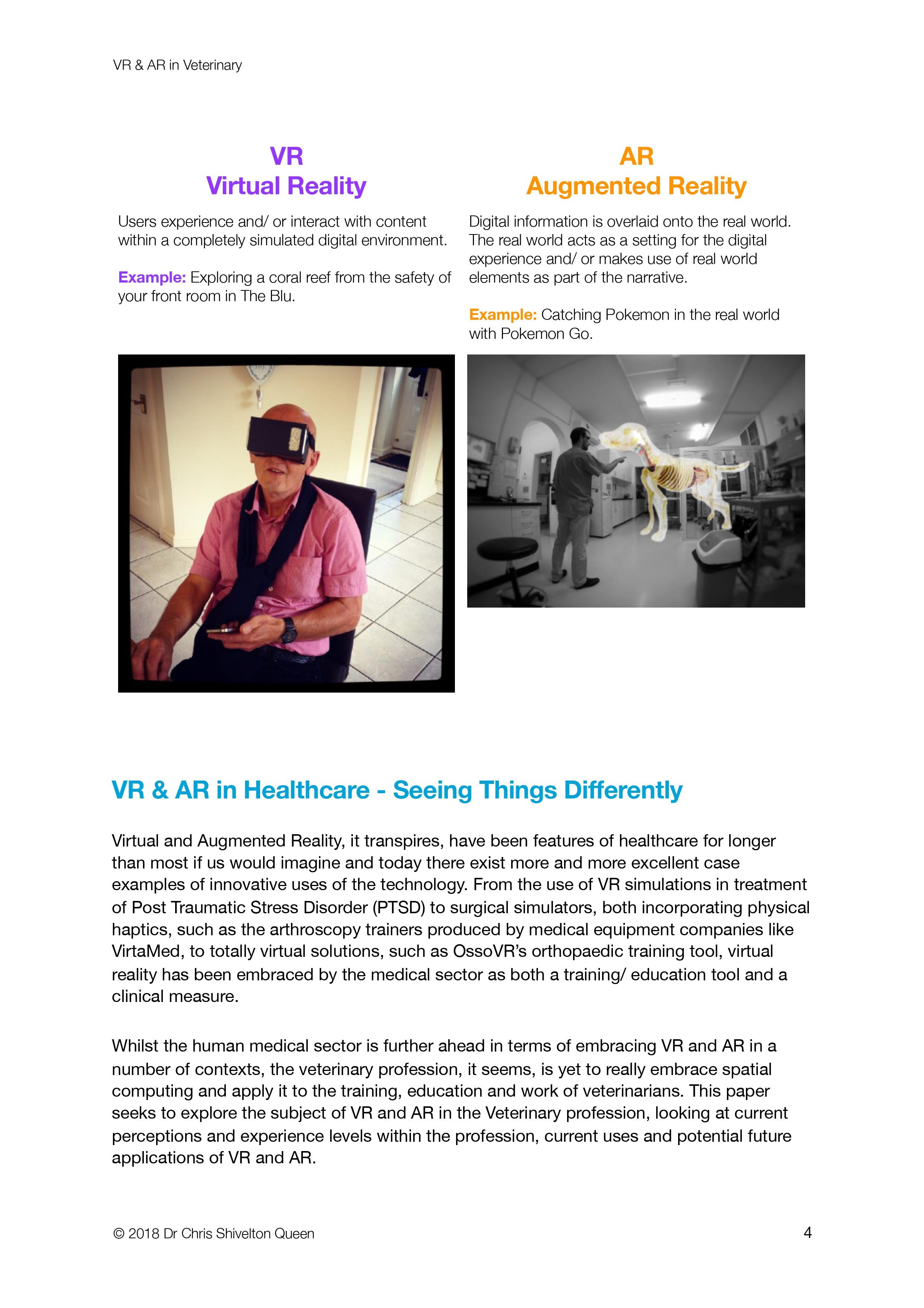

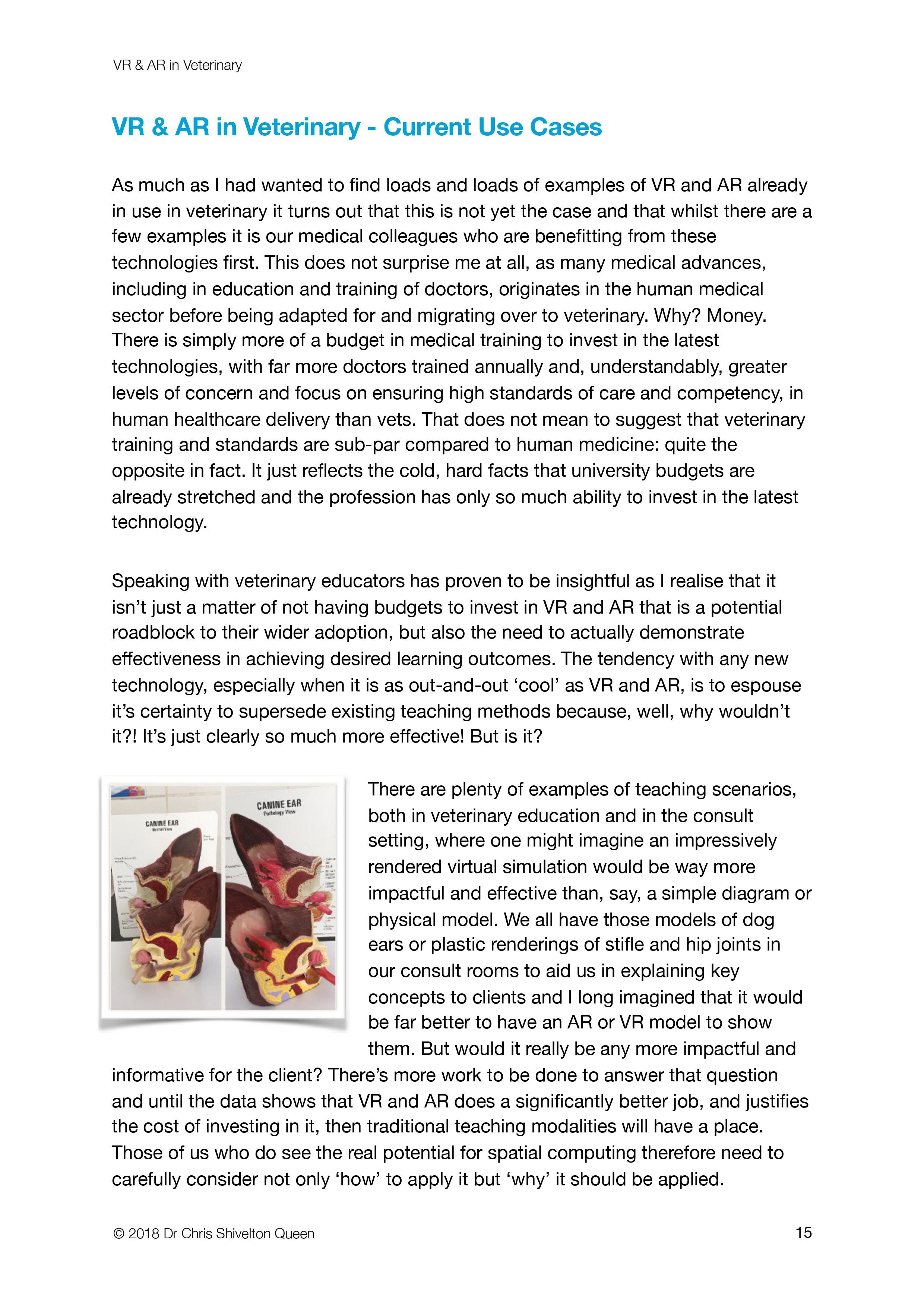

Whilst VR is superb in situations where full immersion in a simulated training environment is preferable, AR lends itself to medical uses where visualisation of intrinsically complex data, such as 3D scan information (CTs, MRI, X-ray), would be of significant utility to clinicians, especially where that data can be overlaid on the actual real-world patient thus providing an entirely enhanced level of context. The difference in clarity of certain medical conditions that are afforded by being able to view clinical data in three dimensions - as they occur in the body incidentally - perhaps whilst being able to easily toggle between layers of relevant information, in addition to being able to consult with colleagues or discuss the case with clients, is marked and some of the very best examples of AR that I have seen in a veterinary capacity have been anatomy training tools, such as Llama Zoo’s Easy Anatomy. This incredibly detailed and accurate application, which is viewable not only in AR but also VR and on standard screens, such as tablets, makes learning canine anatomy that much clearer and intuitive than traditional teaching, potentially offering an alternative to wet-lab dissections, which are labor intensive, complex and expensive to provide, in addition to there being some associated ethical concerns. AR also has real potential in training members of the veterinary team how to use certain key pieces of equipment, such as processing lab samples or setting up an anaesthetic circuit. By essentially annotating the real world in realtime, principles and procedures that might, on paper, appear obscure often achieve an almost instant clarity that significantly enhances the quality and retention of training knowledge.

Artificial Intelligence

There are two key areas where I personally see the greatest value proposition for AI in veterinary. The first is in medical imaging processing and assessment, from rapid yet accurate and sensitive interpretation of radiographs, ultrasound images, MRI and CT scans, right the way through to cytology assessment. As computer processing power, speed and affordability, combined with growth in machine vision reference directories, continues to increase exponentially, it is likely that in the not-too-distant future much of the standard clinical interpretation work that is currently carried out in practice, such as examining a urine sample spin-down for potential crystals or a urinary tract infection, will be delegated to AI, providing veterinarians with rapid, accurate and detailed reports and ensuring a consistency in interpretation that can be lacking in current practice given the difference in experience and skill level between individuals doing the interpretation.

The second area where I see huge potential is in first-line primary consultation. Smart kiosks, such as those developed by AdviNOW Medical in partnership with Akos Med Clinic, already exist for human patients and not only cut down on long waiting times - a significant source of dissatisfaction among patients and a source of stress for over-stretched physicians - but also ensure consistent, accurate and detailed collection of important patient history and physical examination data, all provided and collected by the patient themselves as they are guided through the process by a combination of AI and detailed AR instructions. Once the relevant healthcare data is collected, which typically takes less than 15 minutes, a complete patient work-up, including a breakdown of predicted illnesses and treatment options, is sent to the healthcare provider, who then completes a video consultation to confirm the AI-collected information, verify the diagnosis and confirm or modify the treatment plan. The AI ensures a detailed and accurate healthcare record is maintained and even automatically follows up with patients a few days later. There is already work under way to roll out veterinary-specific versions of this system and it is my belief that it promises to significantly enhance the experience not only of clients and their animals but also improve the working lives of veterinarians, who struggle with the same issues of being chronically overstretched as their human counterparts.

Whilst some fear that technology such as AI will ultimately render human professionals, including veterinarians and medics, redundant I believe that their use, whether VR or AR for training, or AI in helping to automate and improve certain healthcare tasks, will actually enhance the abilities of healthcare professionals. The veterinarian of the future is therefore likely to look as they do today yet possess skills, knowledge and be capable of providing a standard of care and service that far exceeds anything possible in the present. Those poised to gain from this include the clients, animal welfare in general and the profession, which is incredibly exciting.

AUTHOR BIO

Dr Chris Shivelton Queen is a small animal veterinarian who qualified from the University of Bristol with degrees in Veterinary Science and Biochemistry and currently practices in Dubai. He has long had a deep interest in the role technology plays in advancing the veterinary profession, especially Virtual and Augmented Reality. Dr Chris writes and speaks widely on the subject of VR and AR in healthcare and recently spent three months learning VR development skills in Vancouver, Canada, with a view to developing training tools for veterinary professionals. His latest thoughts on the subject can be found at www.thenerdyvet.com.

Virtual Reality in Veterinary

Virtual Reality offers the potential to completely transform how we learn, train and experience aspects of the world that would otherwise be impossible to do so. VR has been a feature of healthcare training for many years, with all the indications being that the pace of adoption and application of this immersive medium to the healthcare sector, including veterinary, is only going to accelerate as the benefits of the tech being clearer.

Virtual Reality offers the potential to completely transform how we learn, train and experience aspects of the world that would otherwise be impossible to do so. VR has been a feature of healthcare training for many years, with all the indications being that the pace of adoption and application of this immersive medium to the healthcare sector, including veterinary, is only going to accelerate as the benefits of the tech being clearer.

Nerdy Vet, Dr Chris Shivelton Queen, has long been a proponent of the use of VR in veterinary education and training, and speaks here about why he remains so bullish on Virtual Reality.

VR in Healthcare

Virtual Reality is already used extensively across a number of sectors for training and education. Healthcare too has already embraced VR. Join Dr Chris Shivelton Queen as he takes you on a journey looking at how VR is currently being used in healthcare and where the future may be taking us.

Virtual Reality is already used extensively across a number of sectors for training and education. Healthcare too has already embraced VR. Join Dr Chris Shivelton Queen as he takes you on a journey looking at how VR is currently being used in healthcare and where the future may be taking us.

Originally presented at the VR in Healthcare Symposium, Washington DC, 2017.

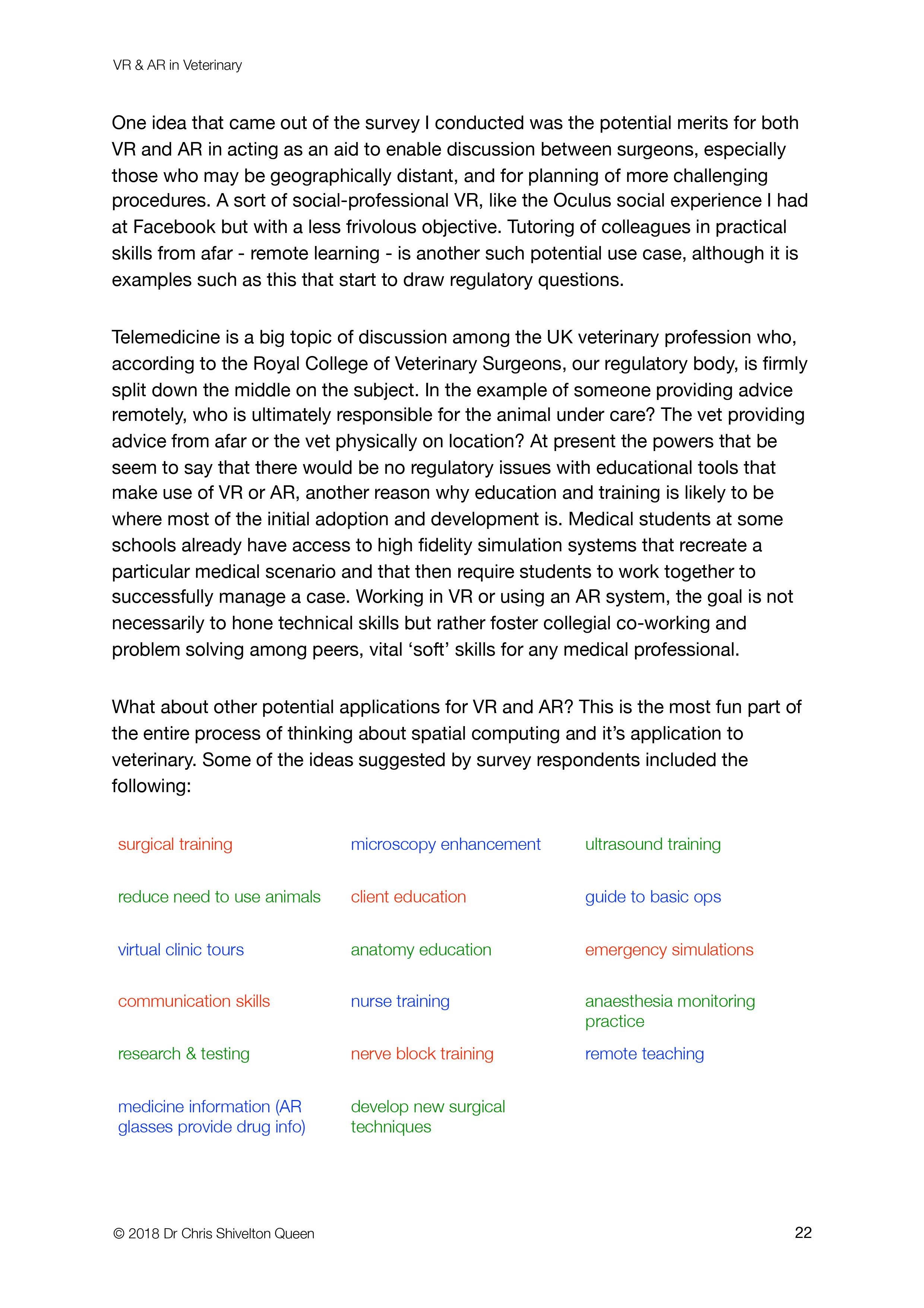

VR and AR in Veterinary

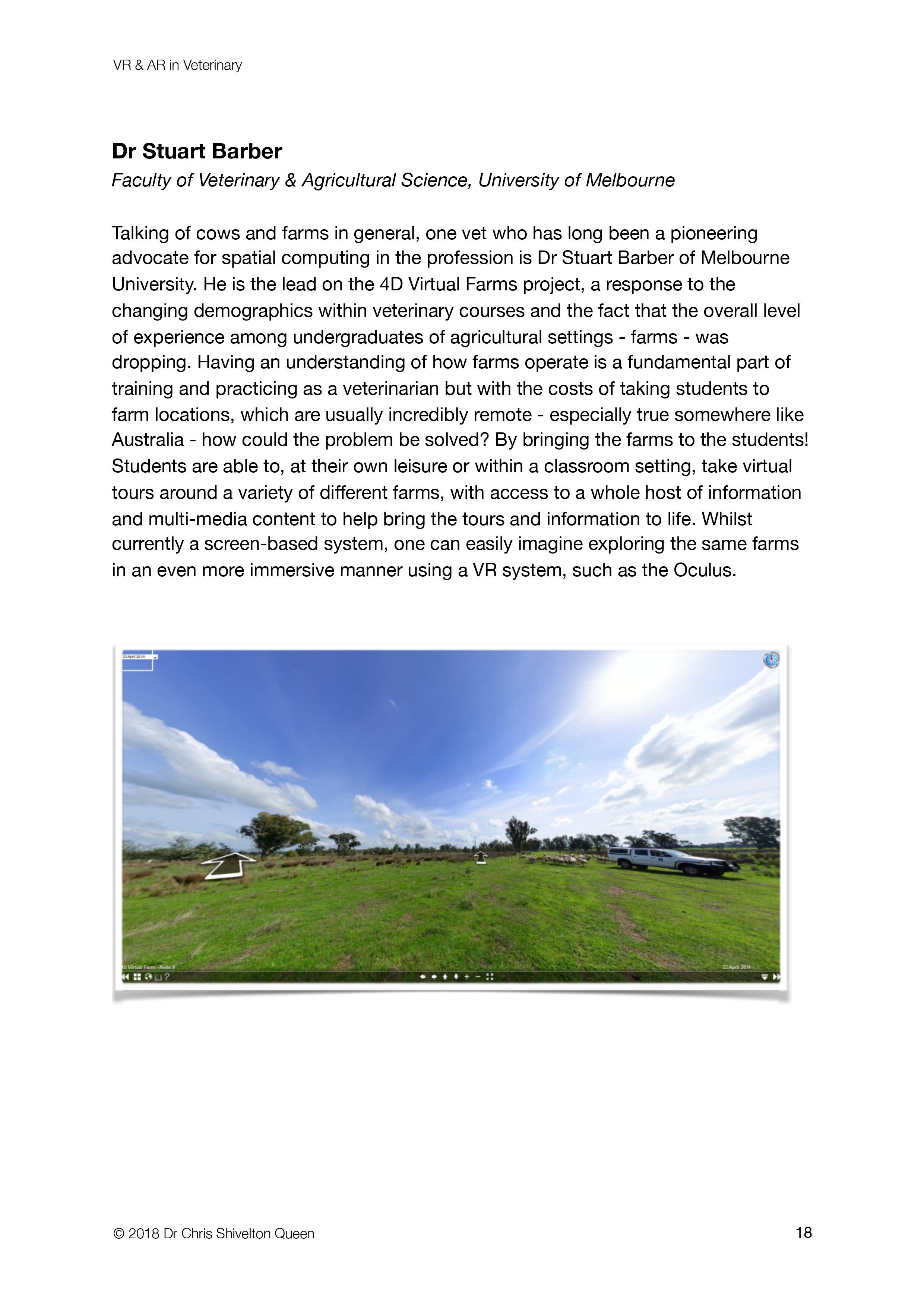

Spatial computing, which incorporates both Virtual Reality (VR) and Augmented Reality (AR) - collectively referred to as Mixed Realty (MR) - is rapidly moving from the realms of science fiction into fact, providing those in healthcare with exciting and interesting new tools for everything from collaboration to education and training. Whilst there are a number of case examples of MR being employed within the human medical sector, it’s use remains in it’s infancy within the veterinary sector.

Spatial computing, which incorporates both Virtual Reality (VR) and Augmented Reality (AR) - collectively referred to as Mixed Realty (MR) - is rapidly moving from the realms of science fiction into fact, providing those in healthcare with exciting and interesting new tools for everything from collaboration to education and training. Whilst there are a number of case examples of MR being employed within the human medical sector, it’s use remains in it’s infancy within the veterinary sector.

Nerdy Vet, Dr Chris Shivelton Queen, explores spatial computing in the veterinary profession, how it's currently being used and where this exciting technology could be taking us in the future.

Presented at the 2018 VR in Healthcare Symposium, Harvard Medical School, Boston, USA.

Messaging & Veterinary

Digital messaging in Veterinary. Is it a wonderful tool or actually a bit of a torment?

Tool or Torment?

As a clinic we started using WhatsApp on our hospital cell phone a couple of years ago in order to provide updates for clients with pets staying in the wards. The ability to quickly and easily send little text updates and occasionally send a cute photo or video of their pet just really helped improve overall communication and engagement with those clients. Sending the occasional picture seemed to really go down well, and still does to this day. “Wonderful,” we thought. “A simple to use, free tool, that actually makes life and our jobs easier.”

That was then. These days, whilst we do still use WhatsApp to keep our hospital patient clients up to date, it has morphed into so much more and not all of it positive. What was once an occasional ping from a client enquiring about how their dog or cat was doing has, at times, felt more like a constant foghorn of message alerts as people ping that phone about everything from requests for repeat prescriptions to unsolicited photos of some obscure part of some unknown body. It has gone from being a welcome tool to feeling more like a torment much of the time.

It is not a surprise that the service is used so much and so often. After all, it is free to use - although that is a point for debate - and also fairly simple. The ability to send certain data, such as location, files, photos and video, has, at many times, made our lives easier. It is, however, this ease of use and lack of a cost that has lead to it becoming a problem. Specifically when it comes to the topic of telemedicine.

What is Telemedicine?

The dictionary definition of the term telemedicine is “the remote diagnosis and treatment of patients by means of telecommunications technology.” It has been a feature of human medicine for many years, with the ability to speak with a healthcare professional remotely and then be diagnosed and prescribed medications to either be posted out or collected by a patient, and whilst there are some limitations, such as the lack of an actual physical examination, the practice has proven very popular, even winning over many skeptics. Veterinary has been behind this telemedicine curve, however, and whilst the recent coronavirus situation has forced the profession to adopt more remote consulting recently, there are a number of pretty compelling reasons why veterinarians have not been permitted to, or even been that enthusiastic, about telemedicine.

“What was that?!”

Animals cannot speak, so cannot describe their clinical signs/ symptoms to the veterinarian.

Limited Information

Human patients can actually talk to their doctors and describe, often in great detail, the nature of their symptoms. For example, they can tell a doctor whether a rash that might well be visible on a video call burns or comes with a different sensation. Such nuanced clinical information can help lead a clinician in whittling down a differential diagnosis list, thus markedly increasing the likelihood of making the correct diagnosis and thus directing treatment most effectively. Our patients, being animals, cannot bring this to a tele-consult: they cannot talk. Yes, we have their owners on hand, as they are in a physical consult room, to offer us their account of the what, when and how of the presenting malady but they cannot offer up the nuanced details that in the absence of a personal description from the patient usually comes from a physical examination. Of course a pet owner may be able to take a rectal temperature, if they are both adequately equipped, confident and prepared to do so, and if their pet permits it, but I, as a vet, am not going to know whether they adequately angled the thermometer to ensure contact with the rectal wall or not - is the temperature they tell me an accurate reflection of body temperature of just that of the pet’s next turd? We could verbally guide an owner as to how to palpate an abdomen but how on earth are they really going to know what it is they’re feeling or, in some important cases, not feeling? What about that subtle little flinch or skin twitch that occurs when performing a physical that would have been imperceptible visually but that our experienced, trained and perceptive fingers and senses picked up on? It is often these ever-so-subtle signs that guide a clinical process and make a doctor just that: a doctor as opposed to a diagnostic algorithm on a device.

Expectations

The nature of tools such as WhatsApp is that they’re ridiculously easy, quick and free to use. The problem is that these same expectations then get translated into the clinical setting and many users expect them to apply there. For example, we get lots of unsolicited messages pinging into our inbox from both known, registered clients and complete strangers that have nothing more than a crappy picture or video and a sentence that essentially asks, “what’s wrong?!” The expectation from most of these people is that a) the response from us should be instant; b) the reply should be a diagnosis, and c) this service should be free. What these people fail to appreciate is the following:

We did not ask for them to send us a clinical enquiry and we do not employ a dedicated clinician to man the WhatsApp line 24/7. If we did then you can absolutely bet your bottom dollar that there would be a charge for using the service. This means that the vets and nurses that are employed by the clinic are usually busy dealing with a patient physically in front of them at the time and so cannot, will not and should not drop what they’re doing to attend to a WhatsApp enquiry. We have, many times, been the recipients of peoples’ ire at the fact that a reply to their message wasn’t sent the instant they sent it themselves, with the charge being, of course, that their enquiry was “urgent.” Well, if it is so urgent then the best thing to do is always call the clinic in order to speak to a human being and to book an appointment.

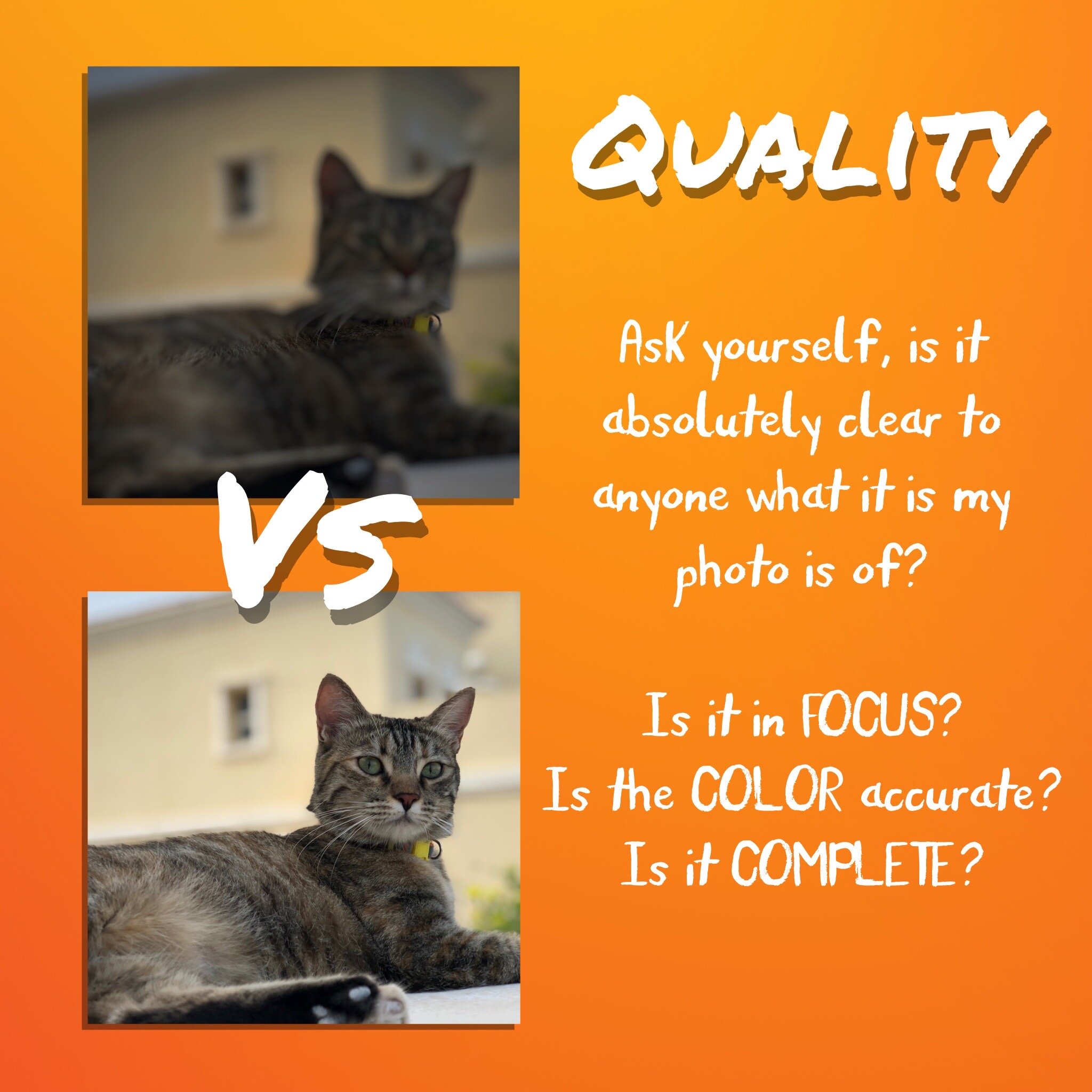

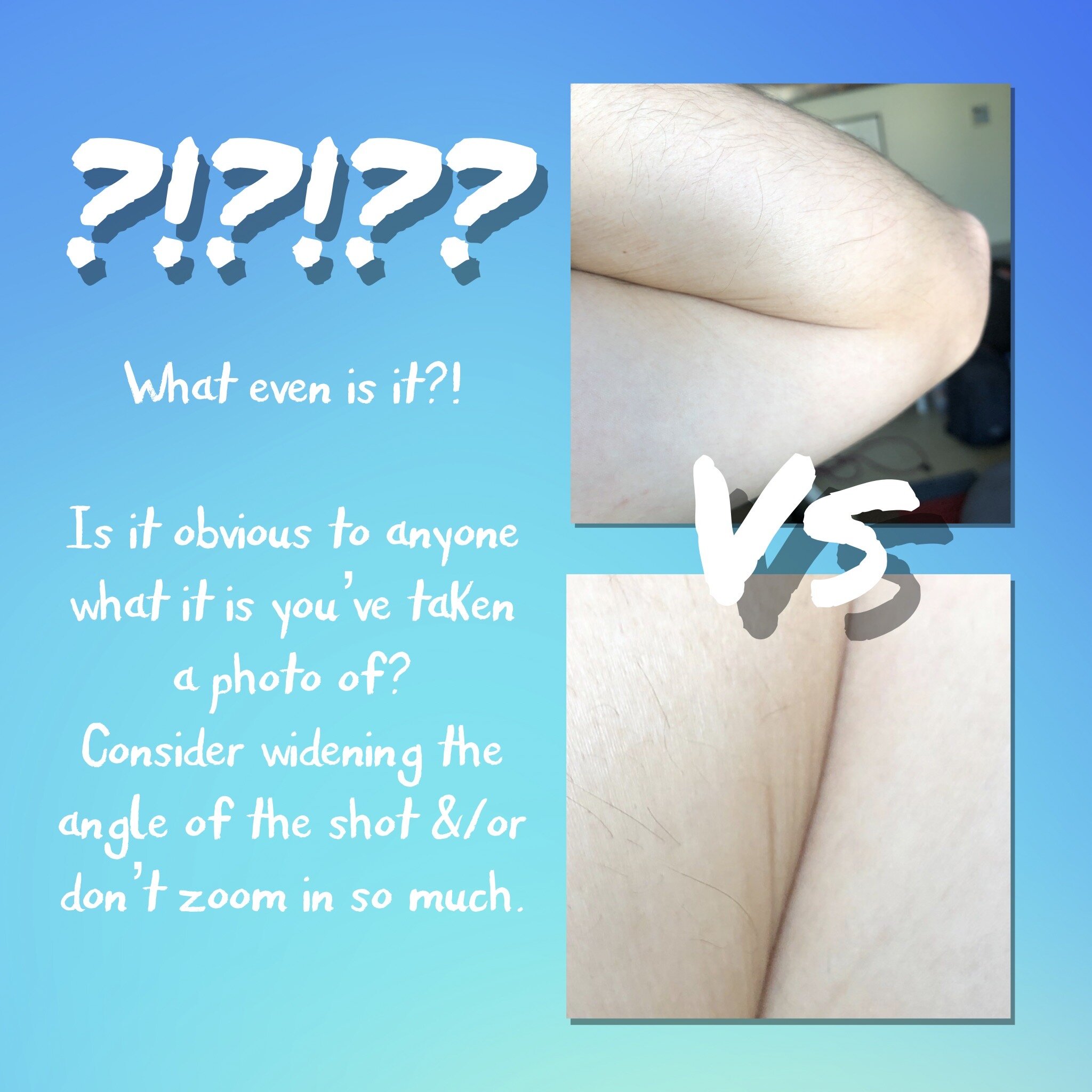

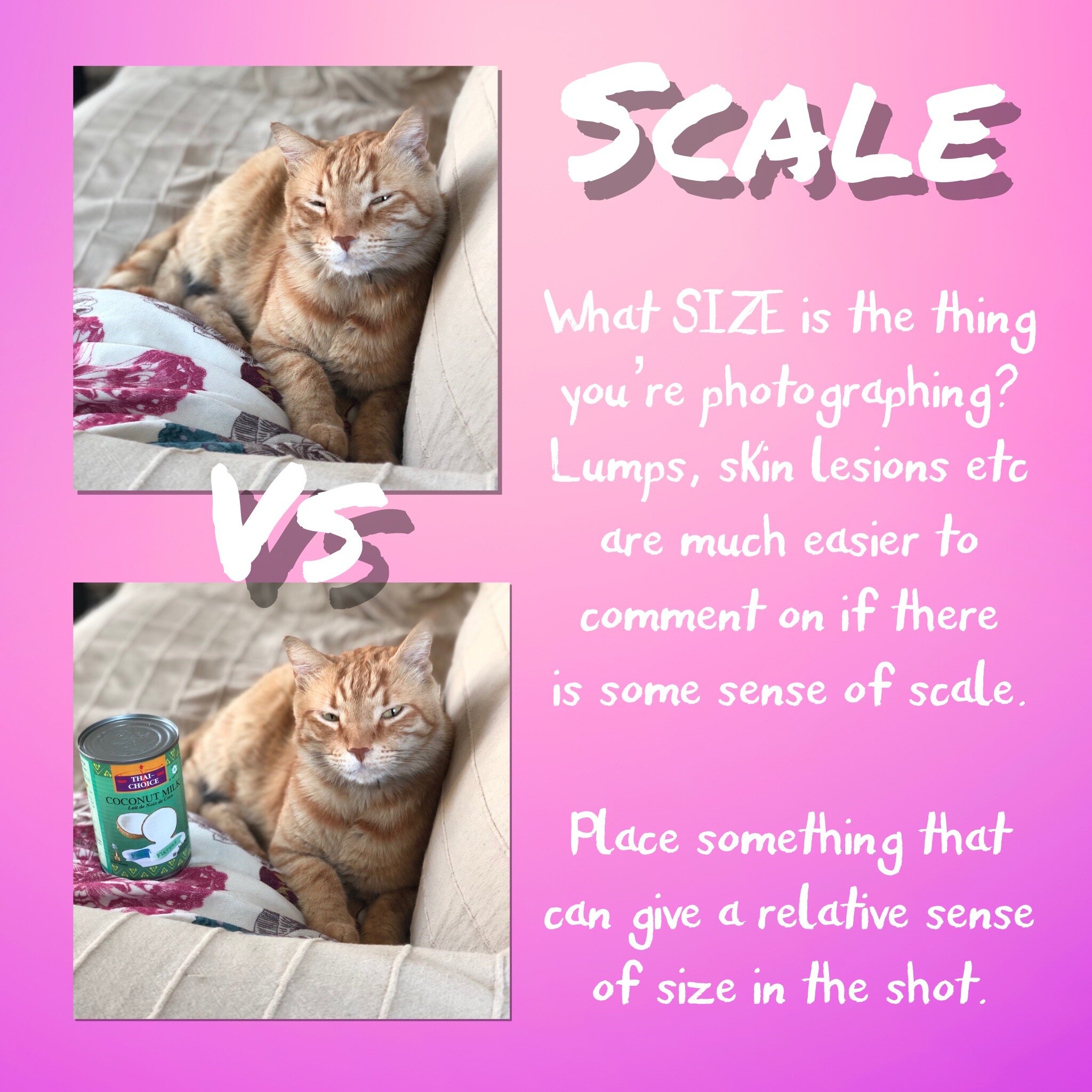

It is extremely difficult to be able to diagnose a clinical problem in an animal solely based on a WhatsApp chat and some ropey video footage or poorly-taken photos. As we’ve already discussed, a physical examination is one of the bedrocks of sound veterinary practice, and it simply isn’t possible via the interwebs! If people do insist on sending us media, and sometimes we may even request them to do so as part of a case’s management, then there are some very simple to apply rules that can dramatically improve the quality of the media sent (see the attached graphics for details).

There are significant costs associated with providing any clinical service: the cost of the actual hospital building, the equipment, the medicines, and the people, including the vets themselves. We charge for our services in order to pay these costs and, hopefully, make some profit to be able to continue investing in the business and make it all worth the while. As such, expecting to receive valuable clinical services for free is not only economically unrealistic but frankly quite insulting. Engaging with clients, both current and new, is a vital and, often, enjoyable part of running and developing a thriving practice and any vet is happy to provide basic information and advice for free, such as on parasite control and the importance of vaccinations. What is not reasonable is to expect a vet to provide a diagnosis of a medical condition, a prognosis and treatment both remotely, on-demand (unless that demand is via a pre-booked appointment) and for free.

How To Use Messaging Without Causing Your Vet To Have a Nervous Breakdown

Whilst it is always preferable to call up a clinic to either request a call-back from a vet or nurse, if it is relevant and appropriate to do so, or to book an appointment if there is a clinical issue, some may still insist on using web-based chat apps like WhatsApp. That’s fine. They’re here to stay and great to use, but in the context of using them in a veterinary capacity, their use should come with some simple caveats.

Don’t expect an instant, or even quick, response to your message. The vets and nurses are almost certainly busy tending to a patient or some other task physically in front of them and the WhatsApp messages will be right down at the bottom of their long priority list. If you want a realtime response, call the clinic.

Don’t expect a diagnosis of a clinical problem. Vets train to examine animals and make diagnoses based on taking detailed histories, observations and physical health exams. They can’t do all of the above via WhatsApp. You’re definitely better off booking an actual appointment with the vet through a call to reception.

Don’t send voice messages. It’s sometimes hard enough deciphering what it is someone wants in a message from the text, let alone trying to decipher some garbled recorded noise. If you’re expecting the vet or nurse to take the time and effort to tend to your enquiry then the least you can do is make the effort to ensure it is intelligible, and this is way, way more likely with written text. If you are going to speak into your phone then you might as well call the clinic and speak directly to a human anyway.

If you do send photos and/or video then please follow the basic guidelines below. They’ll make it much more likely that your enquiry is satisfactorily answered and will save a lot of pointless back-and-forth.