Virtual Reality in Veterinary

Dr Chris shares some nerdy thoughts on how Virtual Reality may impact the veterinary sector.

Dr Chris shares some nerdy thoughts on how Virtual Reality may impact on the veterinary sector.

Messaging & Veterinary

Digital messaging in Veterinary. Is it a wonderful tool or actually a bit of a torment?

Tool or Torment?

As a clinic we started using WhatsApp on our hospital cell phone a couple of years ago in order to provide updates for clients with pets staying in the wards. The ability to quickly and easily send little text updates and occasionally send a cute photo or video of their pet just really helped improve overall communication and engagement with those clients. Sending the occasional picture seemed to really go down well, and still does to this day. “Wonderful,” we thought. “A simple to use, free tool, that actually makes life and our jobs easier.”

That was then. These days, whilst we do still use WhatsApp to keep our hospital patient clients up to date, it has morphed into so much more and not all of it positive. What was once an occasional ping from a client enquiring about how their dog or cat was doing has, at times, felt more like a constant foghorn of message alerts as people ping that phone about everything from requests for repeat prescriptions to unsolicited photos of some obscure part of some unknown body. It has gone from being a welcome tool to feeling more like a torment much of the time.

It is not a surprise that the service is used so much and so often. After all, it is free to use - although that is a point for debate - and also fairly simple. The ability to send certain data, such as location, files, photos and video, has, at many times, made our lives easier. It is, however, this ease of use and lack of a cost that has lead to it becoming a problem. Specifically when it comes to the topic of telemedicine.

What is Telemedicine?

The dictionary definition of the term telemedicine is “the remote diagnosis and treatment of patients by means of telecommunications technology.” It has been a feature of human medicine for many years, with the ability to speak with a healthcare professional remotely and then be diagnosed and prescribed medications to either be posted out or collected by a patient, and whilst there are some limitations, such as the lack of an actual physical examination, the practice has proven very popular, even winning over many skeptics. Veterinary has been behind this telemedicine curve, however, and whilst the recent coronavirus situation has forced the profession to adopt more remote consulting recently, there are a number of pretty compelling reasons why veterinarians have not been permitted to, or even been that enthusiastic, about telemedicine.

“What was that?!”

Animals cannot speak, so cannot describe their clinical signs/ symptoms to the veterinarian.

Limited Information

Human patients can actually talk to their doctors and describe, often in great detail, the nature of their symptoms. For example, they can tell a doctor whether a rash that might well be visible on a video call burns or comes with a different sensation. Such nuanced clinical information can help lead a clinician in whittling down a differential diagnosis list, thus markedly increasing the likelihood of making the correct diagnosis and thus directing treatment most effectively. Our patients, being animals, cannot bring this to a tele-consult: they cannot talk. Yes, we have their owners on hand, as they are in a physical consult room, to offer us their account of the what, when and how of the presenting malady but they cannot offer up the nuanced details that in the absence of a personal description from the patient usually comes from a physical examination. Of course a pet owner may be able to take a rectal temperature, if they are both adequately equipped, confident and prepared to do so, and if their pet permits it, but I, as a vet, am not going to know whether they adequately angled the thermometer to ensure contact with the rectal wall or not - is the temperature they tell me an accurate reflection of body temperature of just that of the pet’s next turd? We could verbally guide an owner as to how to palpate an abdomen but how on earth are they really going to know what it is they’re feeling or, in some important cases, not feeling? What about that subtle little flinch or skin twitch that occurs when performing a physical that would have been imperceptible visually but that our experienced, trained and perceptive fingers and senses picked up on? It is often these ever-so-subtle signs that guide a clinical process and make a doctor just that: a doctor as opposed to a diagnostic algorithm on a device.

Expectations

The nature of tools such as WhatsApp is that they’re ridiculously easy, quick and free to use. The problem is that these same expectations then get translated into the clinical setting and many users expect them to apply there. For example, we get lots of unsolicited messages pinging into our inbox from both known, registered clients and complete strangers that have nothing more than a crappy picture or video and a sentence that essentially asks, “what’s wrong?!” The expectation from most of these people is that a) the response from us should be instant; b) the reply should be a diagnosis, and c) this service should be free. What these people fail to appreciate is the following:

We did not ask for them to send us a clinical enquiry and we do not employ a dedicated clinician to man the WhatsApp line 24/7. If we did then you can absolutely bet your bottom dollar that there would be a charge for using the service. This means that the vets and nurses that are employed by the clinic are usually busy dealing with a patient physically in front of them at the time and so cannot, will not and should not drop what they’re doing to attend to a WhatsApp enquiry. We have, many times, been the recipients of peoples’ ire at the fact that a reply to their message wasn’t sent the instant they sent it themselves, with the charge being, of course, that their enquiry was “urgent.” Well, if it is so urgent then the best thing to do is always call the clinic in order to speak to a human being and to book an appointment.

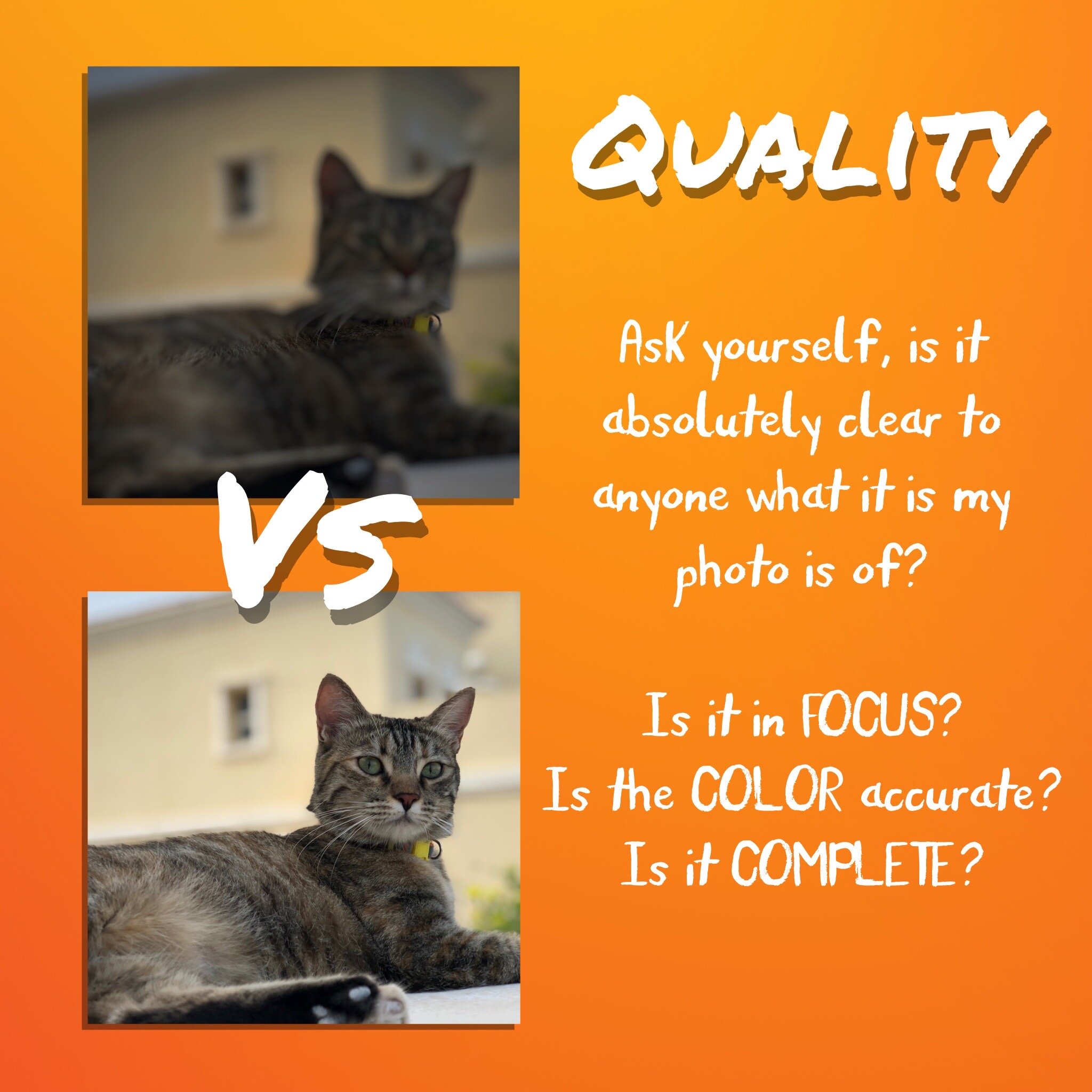

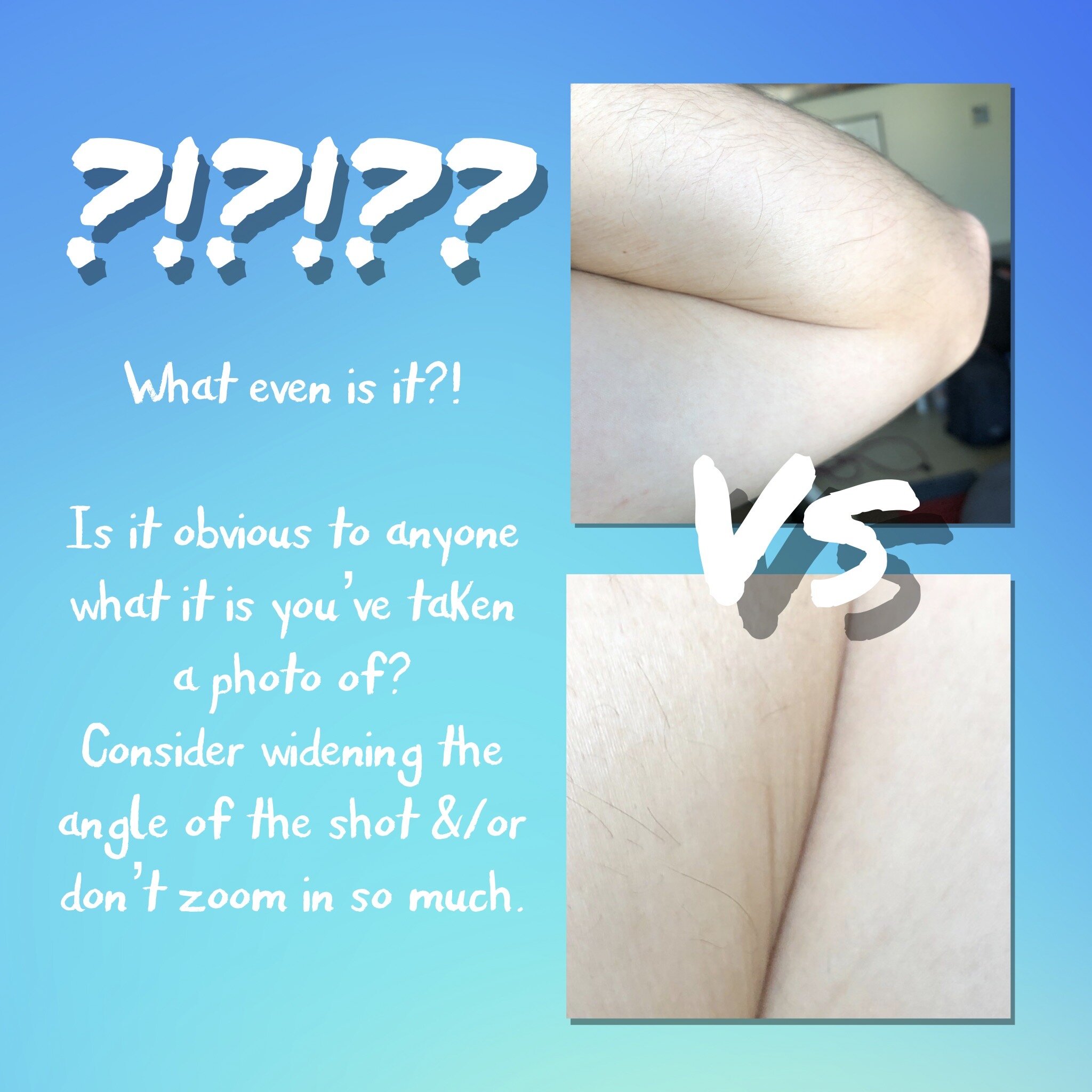

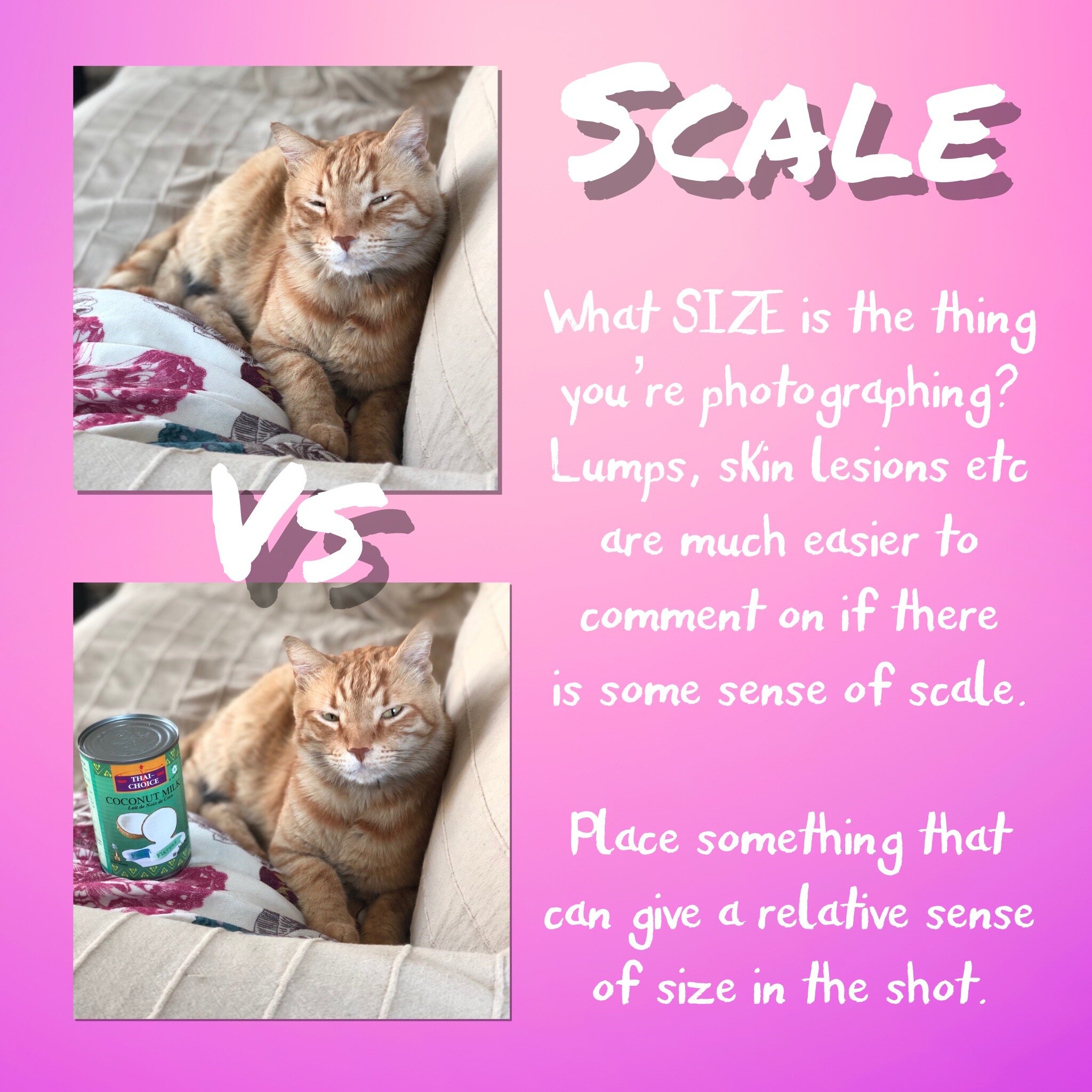

It is extremely difficult to be able to diagnose a clinical problem in an animal solely based on a WhatsApp chat and some ropey video footage or poorly-taken photos. As we’ve already discussed, a physical examination is one of the bedrocks of sound veterinary practice, and it simply isn’t possible via the interwebs! If people do insist on sending us media, and sometimes we may even request them to do so as part of a case’s management, then there are some very simple to apply rules that can dramatically improve the quality of the media sent (see the attached graphics for details).

There are significant costs associated with providing any clinical service: the cost of the actual hospital building, the equipment, the medicines, and the people, including the vets themselves. We charge for our services in order to pay these costs and, hopefully, make some profit to be able to continue investing in the business and make it all worth the while. As such, expecting to receive valuable clinical services for free is not only economically unrealistic but frankly quite insulting. Engaging with clients, both current and new, is a vital and, often, enjoyable part of running and developing a thriving practice and any vet is happy to provide basic information and advice for free, such as on parasite control and the importance of vaccinations. What is not reasonable is to expect a vet to provide a diagnosis of a medical condition, a prognosis and treatment both remotely, on-demand (unless that demand is via a pre-booked appointment) and for free.

How To Use Messaging Without Causing Your Vet To Have a Nervous Breakdown

Whilst it is always preferable to call up a clinic to either request a call-back from a vet or nurse, if it is relevant and appropriate to do so, or to book an appointment if there is a clinical issue, some may still insist on using web-based chat apps like WhatsApp. That’s fine. They’re here to stay and great to use, but in the context of using them in a veterinary capacity, their use should come with some simple caveats.

Don’t expect an instant, or even quick, response to your message. The vets and nurses are almost certainly busy tending to a patient or some other task physically in front of them and the WhatsApp messages will be right down at the bottom of their long priority list. If you want a realtime response, call the clinic.

Don’t expect a diagnosis of a clinical problem. Vets train to examine animals and make diagnoses based on taking detailed histories, observations and physical health exams. They can’t do all of the above via WhatsApp. You’re definitely better off booking an actual appointment with the vet through a call to reception.

Don’t send voice messages. It’s sometimes hard enough deciphering what it is someone wants in a message from the text, let alone trying to decipher some garbled recorded noise. If you’re expecting the vet or nurse to take the time and effort to tend to your enquiry then the least you can do is make the effort to ensure it is intelligible, and this is way, way more likely with written text. If you are going to speak into your phone then you might as well call the clinic and speak directly to a human anyway.

If you do send photos and/or video then please follow the basic guidelines below. They’ll make it much more likely that your enquiry is satisfactorily answered and will save a lot of pointless back-and-forth.